Trust the Process: A Case Study

February 2022 - David Baker

Have you ever watched somebody create a piece of art and struggled to envision what the end-result will look like? Sometimes we need to see it in order to believe it. This can also be applied to the design process of distance learning.

Many academics will have spent their entire careers delivering their modules face-to-face, through traditional methods such as lectures and tutorials. So when they find themselves delivering a DL Program or online Microcredential for the first time, the difference can be quite daunting. Fortunately, Educational Enterprise has experienced Learning Designers who can guide the academics through the design process.

What does a high-quality online course look like?

It's important when designing for online learning that you keep the end-users, the students, in mind. The UX approach that Educational Enterprise has adopted has been praised by academics and students alike. One way to make a course engaging for the students is to provide a wide variety of learning activity types. These activities can usually be broken down into the following categories:

- Acquire (videos, audio, text)

- Discuss (discussion forums, social interaction)

- Investigate (encouraging exploration, timelines, carousels)

- Practice (quizzes, screen recording)

- Produce (written work, reflective documents)

- Collaborate (word clouds, students working together)

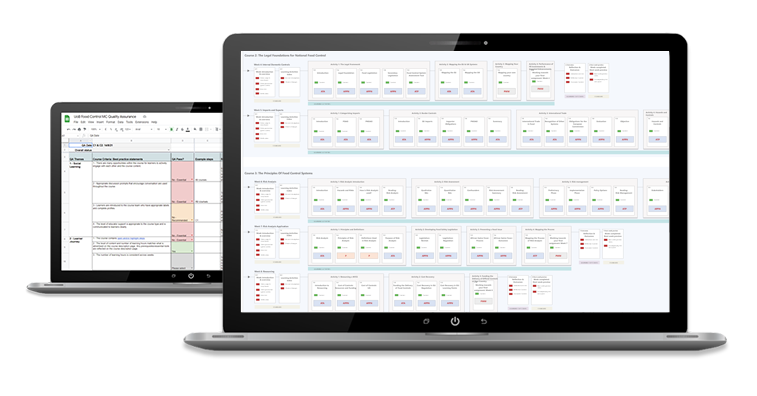

We can measure how much variety we have in our course when building our sitemaps or learner journey maps using our colour-coded matrix. The more variety in colour on the map, the more variety of learning activities in the course.

What happens if you don't follow this process?

When you skip one of the early stages of the design process, the overall build of the course begins to lose focus. For example, if you don’t have a detailed design brief, you don’t have the answers to important questions, such as “Who is this course for?”. If you don’t have a learner journey, then you lack a clear direction of what is to be included in the course, and the balance of learning types can be thrown off.

For example, during the development of one of our microcredential courses, we ran into some issues due to time constraints that meant we were adding content into the course without first agreeing on a finalised learner journey. This meant that when the course was sent off to the platform provider (FutureLearn) for QA, they flagged a lack of variety in learning activity types. This, of course, had to be rectified prior to the launch of the programme.

Initially, the content of the course was heavily video based, featuring lengthy narrated PowerPoints throughout. Had we produced and agreed upon a learner journey map prior to commencing the build, this would have been identified sooner. Once we received the QA feedback, we produced a learner journey to identify areas that could be expanded and diversified, such as adding discussion forums to encourage peer to peer interaction. Revisiting this crucial early step ultimately allowed us to produce a higher quality product that passed the QA inspection.

What did we learn from this?

Following the design process in full is vital to creating a high-quality product. The initial QA feedback for this microcredential serves as a reminder and an example of what happens when you deviate from the process.

When we first began the build, we did not have access to the full development timeline which meant the academic team were unable to fully embrace the process. However, once we were able to demonstrate how we had transformed their traditional-style content into engaging online activities, they were able to incorporate elements of it in their other work.

As we continue to develop courses and programmes for online distance learning, we build a portfolio of examples to show the academics what the final product can look like if they are able to commit to the process.”